Press Release: 1/27/2026

Protecting Massachusetts Revenue: Examining Governor Healey’s Proposed Response to OB3 Federal Corporate Tax Cuts

Key Takeaways

While the governor’s proposal is a meaningful starting point, additional improvements are needed to avoid ineffective and inequitable tax breaks that primarily benefit the wealthiest corporations and investors. The report recommends:

- Fully opting out of the five costliest federal corporate tax changes, rather than delaying them.

- Establishing a stronger process to prevent large federal tax changes from automatically reshaping Massachusetts tax law without deliberate legislative action.

- Eliminating Opportunity Zone tax breaks from the state tax code altogether.

- Ensuring compliance with IRS guidance on Paid Family and Medical Leave without shifting costs onto workers.

While the federal administration aggressively implements its own fiscal policy and budget priorities, states like Massachusetts can protect our own state laws from being reshaped by wasteful and inequitable federal changes.

Last week, Governor Maura Healey took a commendable step towards protecting the Commonwealth from taking the full brunt of the deep tax cuts for corporations that were enacted at the federal level in last summer’s sweeping “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” (OB3). Although Massachusetts’ entire Congressional delegation voted against the federal bill, our state law automatically adopts changes to federal corporate tax rules unless state lawmakers enact legislation to opt out. The Governor has proposed a package of adjustments to the OB3-related changes that would limit the scope of some OB3-related changes and would delay implementation of others. This move would preserve hundreds of millions of dollars of state revenue. The Governor’s package also would create a less abrupt process by which future large federal tax changes could enter the Massachusetts tax code. With the governor’s package as a starting point, state legislators now have the opportunity to make needed improvements to the package that would preserve more state revenue from the federal OB3 changes, avoid ill-advised and ineffective tax breaks for wealthy corporations, and that better protect Massachusetts from future federal tax changes.

The Governor’s Bill Mostly Delays but Does Not Stop the Impact from the Five Largest New Federal Corporate Tax Cuts

Seeing the need to take action early in the year, the Governor filed “An Act to manage federal tax changes in Massachusetts.” The Governor notes in her signing letter to the Legislature that, while the federal legislation adds $4 trillion to the national deficit over the next ten years, the Commonwealth must maintain a balanced budget every year. She notes further that conforming to the OB3 changes would significantly reduce the revenue available to the state budget. Moreover, she notes that other states around the country are making choices about whether or not to implement these federal changes.

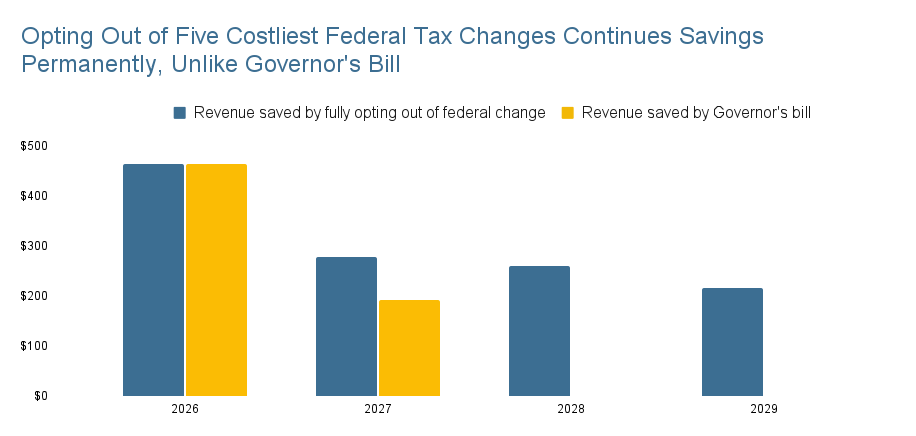

The governor’s bill would not stop the state from automatically adopting the OB3 corporate tax cuts. It would, however, delay state adoption of the five most expensive provisions, as well as making other useful changes. By preventing implementation of all five of these OB3 provisions in the 2025 tax year, the bill also prevents the tax cuts from applying retroactively to past years. The governor’s bill would save the Commonwealth about $463 million in Fiscal Year 2026, based on Department of Revenue estimates of the cost of adopting those provisions.1

Because the governor’s bill does not stop later implementation of these provisions, one of the OB3 changes – “full expensing of domestic research and experimental expenditures” – would begin in Tax Year 2026, costing the state an estimated $87 million in FY 2027. Implementation of the other four changes would likewise begin first in Tax Year 2027, with resulting in combined revenue losses of some $260 million in FY 2028 from the five OB3 changes.2

Eliminating retroactive tax cuts makes sense. Retroactive tax incentives cannot influence corporate investment decisions that already occurred in past years. The effect of retroactive tax cuts is only to enrich the corporate recipients of these cuts at the expense of the commonwealth.

The governor’s bill does not eliminate another major flaw with these corporate federal tax cuts. Whatever one may think about the relative efficacy of using federal tax cuts to encourage corporations to make profitable investments, the same logic does not apply to these tax cuts at the state level. The tax cuts apply to the corporation’s profits, regardless of where the investments were made. Thus, Massachusetts through this tax cut would be rewarding corporations for investments they would make in Texas, Florida, New York, or any other state in the country. A policy like this one won’t effectively incentivize corporations to invest in Massachusetts if it equally rewards them with a tax cut for investing in other states.3

The governor’s bill does address this problem for one of the five corporate tax breaks. The so-called “Opportunity Zones” (OZ) were enacted in the 2017 Trump tax cuts and greatly touted as a way to bring investment to economically depressed areas. In actuality, the OZ program has failed to create many jobs in economically depressed communities. The chief impact is to deliver large tax breaks to wealthy individuals and corporations, including through investments in business and building projects that would have occurred even without the OZ tax break. The Commonwealth currently forgoes tax revenue for investments made in Opportunity Zones in any state, not just in Massachusetts. The governor’s bill would keep this tax break only for OZ investments made in Massachusetts. Unfortunately, Massachusetts cannot legally restrict the other four most costly federal tax cuts only to in-state investments.

While the governor’s bill would reduce and delay the state’s revenue losses from these OB3 changes, the wealthiest investors would still receive enormous benefits from the federal tax cuts. The corporate and individual tax breaks in OB3 altogether will provide an average annual federal tax reduction of $84,800 to the top 1 percent of Massachusetts households (those with incomes above $1.1 million a year). By contrast, the lowest income 20 percent of Massachusetts households (those with incomes below $27,100 a year) will see average federal tax cuts of just $50 each from OB3. High-income households do not need a second round of state-level tax cuts layered on top of the large federal tax cuts they already will receive from OB3.

Other changes proposed by the governor

The legislation proposed by the governor would mirror a strategy used by the state of Maryland to prevent major federal corporate tax changes from being incorporated abruptly into their state tax code. Instead of conforming to federal changes as soon as they are passed at the federal level, the governor proposes that Massachusetts would delay these changes for up to one year if they would increase or decrease state revenue by more than $20 million. This would give lawmakers and interested stakeholders at least some time to recognize and research the new federal tax policies and to discuss and decide which of these are appropriate for the Commonwealth and which are not.

The governor’s bill also would expand a program called the Pass-Through Entity (PTE) excise. The PTE creates a mechanism for Massachusetts residents who have certain types of business income to reduce their federal taxes on that income. As part of the PTE structure, the Commonwealth effectively collects from these taxpayers a small portion of the savings they enjoy on their federal taxes, thus generating a modest amount of additional revenue for the state. This program is popular generally with high-income residents because, collectively, it saves them many hundreds of millions of dollars each year in federal tax payments. According to the Healey administration, the current PTE excise does not allow households who pay the Fair Share surtax to deduct these state taxes from their federal taxable income. The governor proposes allowing the PTE to apply also to the Fair Share surtax, further reducing the federal taxes of these surtax-paying households, while also enabling the Commonwealth to collect an additional $100 million a year, according to estimates from the governor.

The governor’s bill also proposes changes to the funding of Massachusetts’ Paid Family and Medical Leave (PFML) program. These changes to the funding contributions and tax responsibilities of employees and employers are a cause for serious concern and deserve further scrutiny by the Legislature. At first glance the bill would shift significant responsibility for contributing to medical leave costs from large employers onto their workers.

How to improve the Governor’s bill

There are four chief ways to further protect Massachusetts against federal corporate tax changes in OB3, each of which builds on the Governor’s approach:4

- Opting out entirely is better than delay for each of these five, costliest federal tax changes in OB3. Allowing these ineffective and inequitable policies to become part of the state tax code in the near future would result, needlessly, in the loss of some $87 million in FY 2027, growing to a loss of about $260 million in FY 2028, and continued though declining losses in the years thereafter.

- Massachusetts should protect against future federal tax changes abruptly becoming part of our Commonwealth’s tax law. Currently, Massachusetts automatically adopts federal corporate tax changes, big and small, often leaving little time to consider and debate the pros and cons of new federal policies. It makes sense to instead establish a structure that will help lawmakers avoid rushed deadlines when they want to opt out of federal tax changes. Many states have a different approach. Many link parts of their state tax code to the federal tax law as it existed at a particular past year. At a later time, when state lawmakers are ready and better understand the impact of new federal changes, they can update state law to mirror any current federal provisions. The Maryland approach proposed by Governor Healey is somewhat weaker. It freezes adoption of federal changes that have an estimated annual revenue gain or loss above a particular threshold ($5 million in Maryland, or $20 million in the governor’s bill). This is a step in the right direction. However, the Maryland policy automatically adopts federal changes above that set threshold unless state lawmakers enact legislation over the course of a year to prevent it. This approach could be made safer and more deliberate by automatically adopting only those federal corporate tax changes with impact below the threshold. The Commonwealth would not adopt federal changes above the threshold unless legislators take affirmative action to enact these higher-impact changes.

- Opportunity Zones certainly shouldn’t include tax incentives for investments outside of Massachusetts, as the Governor’s bill would ensure. But OZs around the United States have proven to be costly and ineffective. This tax break should be eliminated altogether from the Massachusetts tax code.

- Complying with IRS guidance need not reduce employees’ take-home wages. Instead of shifting the cost of Paid Family Medical Leave onto employees of large businesses, the legislature should adjust the composition of other cost contributions to comply with the new IRS guidance. This can ensure that medical leave benefits remain tax-free for these workers, and costs of funding these important benefits are not shifted from large employers onto their workers.

Appendix

The five most expensive OB3 tax changes from which lawmakers can act to decouple:[3]

- Sec. 70302 (Full expensing of domestic and experimental expenditures) – Allows corporations to deduct 100 percent of their domestic research and experimental expenses in the year in which they incur these expenses. Previously, starting in 2022, corporations were required to spread the deduction for such expenses over a five-year period. DOR estimates Massachusetts will lose $288 million in FY 2026 due to this OB3 change, $87 million in FY 2027, and significantly less in years thereafter. The especially large loss in FY 2026 results from this OB3 change being retroactive back through Tax Year 2022 for businesses with up to $31 million in gross receipts. The Governor’s bill would eliminate the retroactive tax break and would avoid major revenue losses in FY 2026. The OB3 change, however, would be implemented beginning in Tax Year 2026 and would result in significant revenue losses in FY 2027 and thereafter.

- Sec. 70307 (Special depreciation allowance for qualified production property) – This change expands the definition of corporate expenses that qualify for “100 percent bonus depreciation.” Historically, corporations have been allowed to write off 100 percent of the cost of machinery and equipment investments in the year those investments are made, rather than gradually, over the expected lifetime of the investment. This OB3 change adds factory buildings to the list of qualifying investments. DOR estimates this change will cost Massachusetts $98 million in FY 2026, approximately $120-130 million annually in FY 2027 through FY 2029, then drops significantly in cost thereafter. It is retroactive back to the start of Tax Year 2025 though that feature would be eliminated by the governor’s bill, which would delay implementation of this tax break until Tax Year 2027.

- Sec. 70303. (Modification of limitation on business interest) – The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) set a limit on how much of the interest that corporations pay on their loans could be deducted from the corporation’s taxable income. Limiting deductibility keeps corporations from leveraging debt as a way to reduce their tax bills – a tax avoidance strategy employed particularly in many private equity deals. Under TCJA, corporations with sales above $25 million per year could deduct interest equal to 30 percent of their pre-tax profits. In 2021, this limit was tightened. OB3 permanently returns to the looser TCJA rules for large corporations. DOR estimates Massachusetts will lose $52 million in FY 2026 due to this OB3 change and some $20-25 million per year thereafter. It is retroactive back to the start of Tax Year 2025 though that feature would be eliminated by the governor’s bill, which would delay implementation of this tax break until Tax Year 2027.

- Sec. 70306. (Increased dollar limits for expensing depreciable business assets) – While 100 percent bonus depreciation has been available only intermittently over the years, businesses have long been permitted to deduct immediately the full cost of certain types of purchases, such as furniture, computers, and manufacturing equipment. OB3 raises the limits on the dollar amount of such items that can be fully deducted in the year they are purchased. DOR estimates this change will cost $25 million in FY 2026 and significantly less thereafter. It is retroactive back to the start of Tax Year 2025 though that feature would be eliminated by the governor’s bill, which would delay implementation of this tax break until Tax Year 2027.

- Sec. 70421. (Permanent renewal and enhancement of opportunity zones) – As part of TCJA, a new “Opportunity Zones” (OZ) program was created, with the intended purpose of incentivizing investments in job-generating businesses and in buildings in areas designated as economically depressed. Capital gains income generated by corporations or individuals from investments made in OZs became eligible for extremely generous tax breaks, including being exempted entirely from tax if the investments were held for 10 years. Set to expire at the end of 2026, under OB3 the program instead will become permanent. It has become clear, however, that the OZ program has failed to create many jobs in economically depressed communities. What it has done is deliver large tax breaks to wealthy individuals and corporations, including through investments in business and building projects that would have occurred even without the OZ tax break. To the extent that tax breaks play any role in these investment decisions, it is the much larger federal OZ tax breaks that will drive such investments. DOR estimates this OB3 change will cost the Commonwealth $20-30 million a year starting in FY 2027. The governor’s bill would reduce this cost somewhat by providing the tax break only for qualifying investments made in Massachusetts Opportunity Zones.

Endnotes

1 The administration’s estimates describe the state revenue impact of OB3 by fiscal year, which do not match neatly with tax years and leave some uncertainty over the timing of the impact of policy alternatives.

2 These costs are based on whether or not the state has adopted a federal tax provision for state taxes in a particular year. As discussed below but not represented in the chart, the Governor would also limit eligibility for the Opportunity Zones tax break to investments in Massachusetts. This would save a considerable portion of the roughly $18 million to $33 million annual revenue loss projected from this tax cut in the next few years.

3 Given Single Sales Factor apportionment, the portion of corporate profits subject to tax is due to the portion of sales in Massachusetts, not the location of a corporation’s workforce or assets. Reducing the taxation of businesses does nothing to encourage location of assets and employment in Massachusetts.

4 Though outside the scope of this analysis, the bill would also increase the threshold at which people are required to report and pay taxes on gambling winnings.