Press Release: 12/1/2025

Global Emissions Limitation Framework

This post collects materials pertaining to international agreements intended to reduce carbon emissions. The post focuses on legal structures and national commitments as opposed to the related scientific understanding. A future post will collect materials on the science behind the agreements.

Framework Convention on Climate Change

Essentially every nation in the world has become a party to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, originally signed in Rio de Janeiro in 1992. There are currently 198 parties to the UNFCCC, including the United States. The U.S. Senate ratified the convention in October 1992 and President Trump’s January 2025 executive order withdrawing from Paris Agreement did not withdraw the United States’ status as a party to the UNFCCC (although it did purport to revoke any financial commitments under the UNFCCC).

The framework

The UNFCCC is essentially a commitment to work together to address climate change:

The ultimate objective of this Convention . . . is to achieve, . . . stabilization of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system. Such a level should be achieved within a time-frame sufficient to allow ecosystems to adapt naturally to climate change, to ensure that food production is not threatened and to enable economic development to proceed in a sustainable manner.

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, Article 2

The convention does not set specific climate goals or create binding emission targets. It affirms national sovereignty while also acknowledging mutual responsibilities:

[S]tates have, in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations and the principles of international law, the sovereign right to exploit their own resources pursuant to their own environmental and developmental policies, and the responsibility to ensure that activities within their jurisdiction or control do not cause damage to the environment of other States or of areas beyond the limits of national jurisdiction,

While stating this universally applicable principle, the convention also recognizes the asymmetry between developing and developed countries, which are specifically identified in Annex 1 to the convention:

[T]he largest share of historical and current global emissions of greenhouse gases has originated in developed countries, . . . per capita emissions in developing countries are still relatively low and . . . the share of global emissions originating in developing countries will grow to meet their social and development needs.

The developed country Parties . . . shall . . . take . . . measures . . . limiting . . . emissions of greenhouse gases . . . [that] demonstrate that they are taking the lead in modifying longer-term trends.

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, Preamble and Article 4, Section 2(a)

Specific obligations in the framework convention

The convention, while not specific as to emissions goals or investment amounts, does include a set of general commitments by parties, among them:

- Develop, update, and share national inventories of greenhouse gas emissions sources

- Formulate and implement measures to mitigate climate change [reduce emissions]

- Cooperate in preparing for adaptation to climate change

- Support research and observation related to the climate system

- Developed country Parties are to “provide new and additional financial resources” to assist developing country parties

Conference of the Parties

Article 7 of the convention sets up a Conference of the Parties (COP) to continue conversations — reviewing evolving science, reviewing actions taken, considering further legal commitments and publishing findings. Article 8 sets up a secretariat to administer the proceedings of the Conference of the Parties. The Conference of the Parties has met 30 times since its establishment in 1992. The principal further agreements yielded by the COP are the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement.

The Kyoto Protocol

Conversations through the COP yielded the Kyoto Protocol on December 11, 1997. The Kyoto protocol, for the first time, included specific emission reduction commitments. Commitments were articulated as the ratio between emissions during the years 2008 through 2012 and a base year. For the United States, the ratio was 93% and the base year was 1990; in other words, U.S. emissions on average during the years 2008 through 2012 were to be 7% below 1990 emissions. Paragraphs 3 and 6 of Article 3 make clear that carbon emissions should be netted against carbon sinks like new forestation. The 32-page protocol includes mechanisms to assure clarity, transparency, and verification.

The Clinton administration signed the treaty on behalf of the United States in November 1998. However, the U.S. Senate never ratified it. In fact, in July 1997 (five months before Kyoto negotiators finalized language), the Senate passed the Bird-Hagel resolution disagreeing fundamentally with the then-emerging treaty approach. The treaty was expected to impose binding emission-control obligations only on developed nations, as opposed to developing nations. The Senate Resolution 98 (105th Congress) expressed the view that:

The United States should not be a signatory to any protocol to, or other agreement regarding, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change of 1992, at negotiations in Kyoto in December 1997, or thereafter, which would — (A) mandate new commitments to limit or reduce greenhouse gas emissions for the Annex I Parties, unless the protocol or other agreement also mandates new specific scheduled commitments to limit or reduce greenhouse gas emissions for Developing Country Parties within the same compliance period, or (B) would result in serious harm to the economy of the United States; . . .

S. Res. 98, 105th Congress

The U.S. Senate voted 95-0 in favor of this resolution. ‘Yes’ votes included Massachusetts Senators Kennedy and Kerry. So, the entire Senate effectively rejected the emerging Kyoto framework, but that rejection did not alter the course of negotiations and the final treaty took the approach that the U.S. Senate had already rejected. In a letter to Senators sent in March 2001, the new George Bush administration specifically disclaimed support for the Kyoto Protocol.

Looking back on the United States’ emissions trajectory, according to the EPA’s inventory of greenhouse gas emissions and sinks at table 2-1, U.S. net emissions continued to climb from 1990 through 2004, peaking at 19% above 1990 levels. After 2007, U.S. net emissions began to decline, returning to approximately 1990 levels by 2016 and remaining roughly level since then. U.S. net emissions in 2022 were 1% below 1990. In other words, the United States did not come close to meeting the 7% reduction from 1990 that would have been required by Kyoto in the 2008-2012 period after that period. Numerical details here.

For comparison, from the UN Greenhouse Gas Inventory, we can see that the other developed countries (Annex I countries excluding the United States and also excluding the former soviet economies in transition) did make material progress towards meeting their Kyoto target for 2018-2012. Those countries had a collective reduction target of 5.4% from 1990 to the 2008-2012 period. Their emissions were down 4.1%. See Annex B to the Protocol and numerical details here. An extension of Kyoto, the Doha Amendment, set a target of 20% reduction from 1990 for average emissions in the 2013-2020 period for those countries. Those countries’ emissions came in 10% below 1990 levels during this period, but not all joined the Doha extension. These contrasts between the U.S. and the other developed countries omit any adjustment for factors like population growth, deindustrialization, etc.

The Paris Agreement

The mixed results from Kyoto led to a new approach in the next agreement negotiated by the Conference of the Parties — 2015 Paris agreement. This agreement defines a carefully-worded compromise goal for climate protection:

Holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, recognizing that this would significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change;

Paris Agreement, Article 2, ¶1(a)

This is a values-based political compromise about acceptable harm levels. The compromise is informed by scientific assessment, but it is not a scientific finding per se. See this discussion of the evolution of goals before Paris.

To this end, the Agreement defines a desired emissions trajectory leading to global net zero emissions “in the second half of this century.”

Parties aim to reach global peaking of greenhouse gas emissions as soon as possible, recognizing that peaking will take longer for developing country Parties, and to undertake rapid reductions thereafter in accordance with best available science, so as to achieve a balance between anthropogenic emissions by sources and removals by sinks of greenhouse gases in the second half of this century, on the basis of equity, and in the context of sustainable development and efforts to eradicate poverty. . . .

Developed country Parties should continue taking the lead by undertaking economy-wide absolute emission reduction targets. . . .

Paris Agreement, Article 4, ¶1 and ¶4

Although it defines a compromise temperature goal, recites a desired global emissions trajectory, and embraces emissions reduction targets for developed nations, the Paris agreement does not define emission targets for any nation, rather leaving each nation to specify their own chosen contribution — the “Nationally Defined Contribution” or “NDC.” The agreement merely exhorts nations to be “ambitious:”

As nationally determined contributions to the global response to climate change, all Parties are to undertake and communicate ambitious efforts . . . with the view to achieving the purpose of this Agreement . . . . The efforts of all Parties will represent a progression over time, while recognizing the need to support developing country Parties for the effective implementation of this Agreement.

Paris Agreement, Article 3

In the summary decision document for the Paris conference, a document which wraps around the Paris Agreement,

the Conference of the Parties . . . reiterates its invitation to all Parties that have not yet done so to communicate to the secretariat their intended nationally determined contributions and . . . notes with concern that the estimated aggregate greenhouse gas emission levels in 2025 and 2030 resulting from the intended nationally determined contributions do not fall within least-cost 2° C scenarios . . .

1/CP.21 (Decision 1, Conference of the Parties 21)

In addition to the emissions related provisions, the Paris Agreement speaks in general, non-binding terms to:

- Adaptation, “enhancing adaptive capacity, strengthening resilience . . .” (Article 7)

- Averting loss and damage associated with extreme weather events (Article 8)

- Developed country support of adaptation and mitigation measures in developing countries (Article 9)

- Technology development and transfer (Article 10)

- Climate education, training, public awareness (Article 12)

- Transparency as to emissions and emission mitigation measures (Article 13)

Conferences of the Parties Since Paris

There have been Conferences of the Parties annually since Paris. Conferees have continued to monitor and discuss the Nationally Defined Contributions contemplated by the Paris Agreement. At this point, 318 new or updated NDCs have been submitted to the NDC registry. Yet, the conferences have recognized and lamented a growing gap between the NDCs and emissions reduction necessary to achieve the Paris climate goals.

For example the conference report for Glasgow in 2021, stated that the Conference of the Parties:

. . . Expresses alarm and utmost concern that human activities have caused around 1.1 °C of warming to date . . .

. . . Reaffirms the Paris Agreement temperature goal of holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels . . .

. . . Recognizes that limiting global warming to 1.5 °C requires rapid, deep and sustained reductions in global greenhouse gas emissions, including reducing global carbon dioxide emissions by 45 per cent by 2030 relative to the 2010 level and to net zero around mid-century as well as deep reductions in other greenhouse gases . . .

. . . Notes with serious concern [that] the aggregate greenhouse gas emission level, taking into account implementation of all submitted nationally determined contributions, is estimated to be 13.7 per cent above the 2010 level in 2030.

. . . Emphasizes the urgent need for Parties to increase their efforts to collectively reduce emissions through accelerated action and implementation of domestic mitigation measures . . .

Report of the Conference of the Parties, Glasgow, 2021

The December 2023 “Global Stocktake,” held in the United Arab Emirates resulted in a report making statements similar to the above:

The Conference of the Parties . . .

. . . notes with concern the pre-2020 gaps in both mitigation ambition and implementation by developed country Parties and that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change had earlier indicated that developed countries must reduce emissions by 25–40 per cent below 1990 levels by 2020, which was not achieved;

. . . notes with concern the findings in the latest version of the synthesis report on nationally determined contributions that implementation of current nationally determined contributions would reduce emissions on average by 2 per cent compared with the 2019 level by 2030 and that significantly greater emission reductions are required to align with global greenhouse gas emission trajectories in line with the Paris Agreement temperature goal and recognizes the urgent need to address this gap . . .

Report of the Paris Agreement’s Fifth Session, Global Stocktake Outcomes, ¶¶17,21 (FCCC/PA/CMA/2023/16/Add.1)

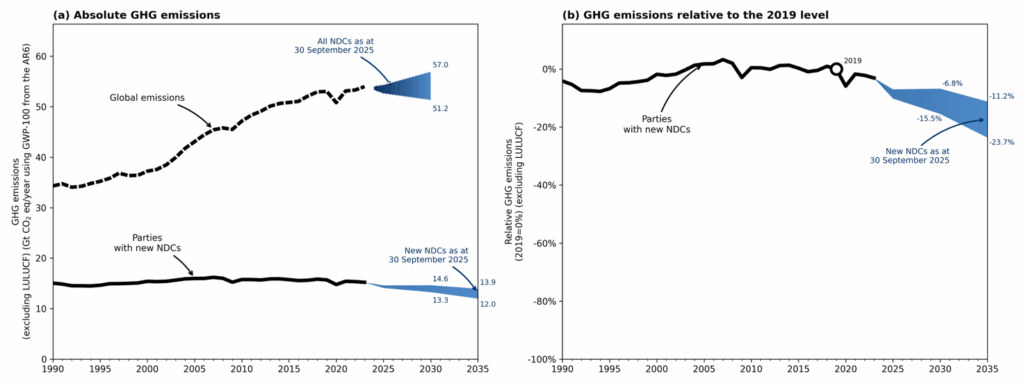

The most recent synthesis report on Nationally Determined Contributions under the Paris Agreement, dated October 28, 2025, focused primarily on the “64 new NDCs . . . recorded in the NDC registry between 1 January 2024 and 30 September 2025, covering about 30 per cent of total global emissions in 2019.” Even as to these 64 parties submitting new NDCs, the recent report concludes that the 2035 reductions fall short of the depth found by the International Panel on Climate Change to be necessary to achieve the Paris Accord climate goals — see paragraphs 211 through 213.

[I]n order to be in line with global modelled pathways to limiting warming to 1.5 C (with over 50 per cent likelihood in 2100) . . . GHG emission reductions will have to be reduced by 60 (49–77) per cent by 2035 relative to the 2019 level . . .. For 2040 and 2050, further emission reductions will be needed . . . including achieving net zero CO2 emissions by 2050 (a 99 per cent CO2 emission reduction relative to the 2019 level). With their GHG emissions in 2035 on average estimated to be 17 (11–24) per cent below their 2019 level . . ., the scale of the total emission reduction expected to be achieved by the group of Parties (noting that this is only about 33 per cent of Parties to the Paris Agreement) through implementation of their new NDCs falls short of what is necessary according to the IPCC ranges . . ..

2025 synthesis report on Nationally Determined Contributions under the Paris Agreement, ¶¶212-213.

Most of the 2025 synthesis report focuses on characteristics of the new NDCs, but the top line in the left hand graph below (copied from the report) shows the big picture on global emissions, including all NDCs in place as of September 30, 2025. That graph shows essentially no reduction in global emissions from 2015 to 2030 based on all NDCs. Framing the findings more hopefully, one could conclude that emissions may peak before 2030.

Figure 22 from 2025 Synthesis Report: Global emissions and aggregate emissions of Parties that submitted new nationally determined contributions

Copied from 2025 Synthesis Report, page 53.

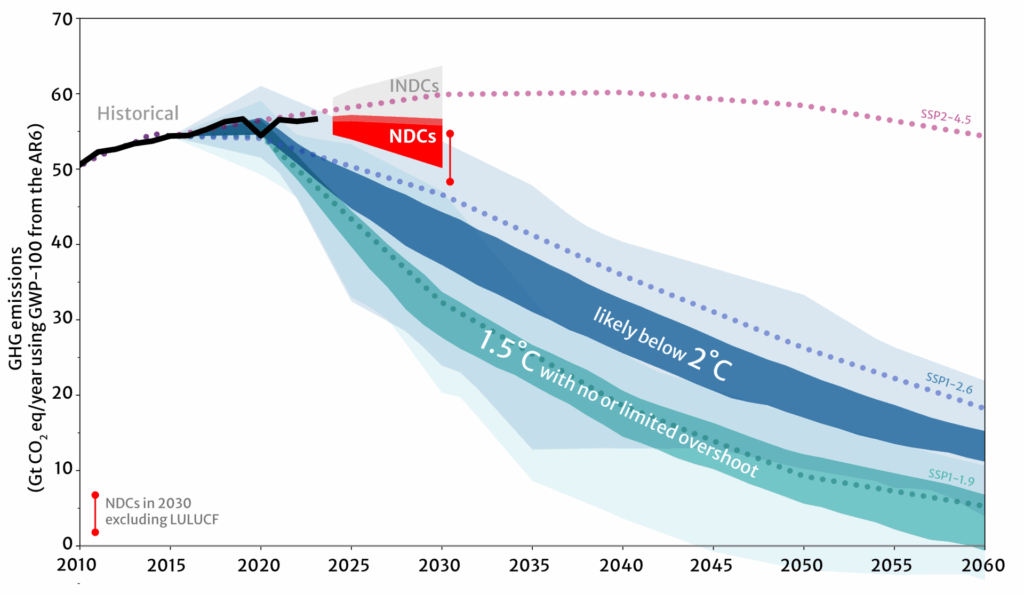

The earlier 2024 Synthesis report included the graphic below comparing the trajectories necessary to keep warming below 1.5 or 2 degrees Centigrade (Teal and Blue) with the trajectory of emissions reductions expected based on the then-registered NDCs (range in solid red). Note that the dotted red “INDC” line reflects weaker “Intended Nationally Defined Contributions” in place in 2016 — the Paris NDCs do represent progress over the INDCs.

Copied from 2024 Synthesis Report, Web Version. See also fuller explanatory notes full report, figure 8, page 29.

Interpreting this graphic, the report emphasizes the gap between expected emissions and the reductions necessary to limit global temperature increase:

The absolute difference in the level of emissions by 2030 according to the latest NDCs and these IPCC scenarios is sizeable, despite progress compared with the level according to the INDCs as at 4 April 2016. The difference between the projected emission levels that do not take into account implementation of any conditional elements of NDCs and the emission levels in the scenarios of keeping warming likely below 2 °C (with over 67 per cent likelihood) by 2030 is estimated to be 14.9 (10.9–18.3) Gt CO2 eq. In relation to the scenarios of limiting warming to 1.5 °C (with over 50 per cent likelihood) and achieving net zero emissions this century, the gap is even wider, at an estimated 22.7 (21.2–27.7) Gt CO2 eq. However, assuming full implementation of all latest NDCs, including all conditional elements, the gap is slightly narrowed, towards 11.3 (7.3–14.7) Gt CO2 eq in relation to the aforementioned 2 °C scenarios and towards 19.2 (17.6–24.1) Gt CO2 eq in relation to the aforementioned 1.5 °C scenarios.

2024 Synthesis Report, Web Version. For more explanation, see full report, circa figure 8, page 29.

To fully unpack these statements about necessary emissions trajectories, it is necessary to turn to the reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change — to be reviewed in a future post.

United States Nationally Determined Contribution (withdrawn)

Shortly prior to President Trump’s taking office in January 2025, the Biden administration, on December 19, 2024, did submit a Nationally Determined Contribution to the NDC registry:

The nationally determined contribution of the United States of America is: To achieve an economy-wide target of reducing its net greenhouse gas emissions by 61-66 percent below 2005 levels in 2035.

US NDC

Note that a 65% reduction from 2005 levels equates to a 59% reduction from 1990 levels. When President Trump took office he issued an executive order withdrawing from Paris Agreement. For a review of the withdrawal, see this Congressional Research Service Report.

Additional Resources

- CRS report The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, the Kyoto Protocol, and the Paris Agreement: A Summary.

- UN Environment Programme, Emissions Gap Report 2024